|

|

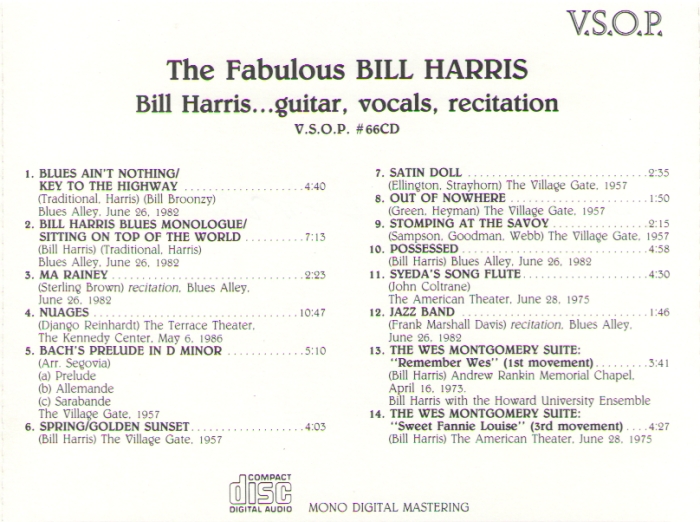

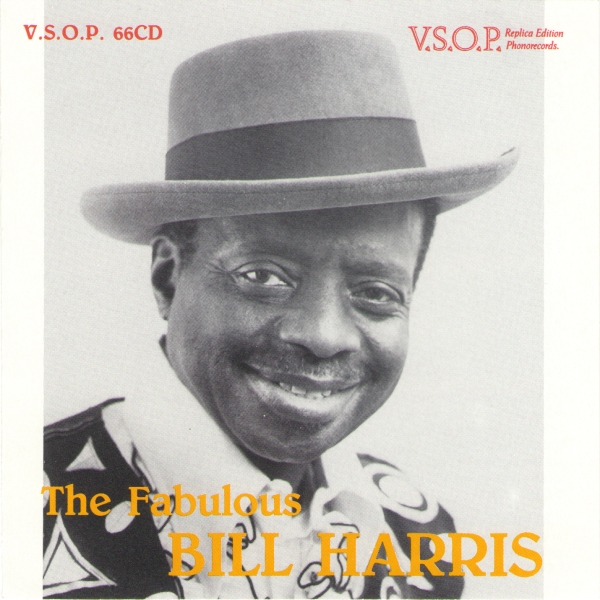

V.S.O.P. 66 CDTHE FABULOUS BILL HARRIS guitar, vocals, recitation

As this CD was being produced back in 1988, Bill Harris was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, and his prognosis was not promising. He had decided to stop chemotherapy and radiation therapy, as the odds of his surviving for any length of time were very low. He was trying various homeopathic remedies, while he was still ambulatory, but he was resigned to face what seemed inevitable. Completing the CD was a race with the grim reaper. As a result, the explanation of what this CD was really about was neglected. This was due in part to the fact that the primary audience for this album was local. None of Bill Harris’s other works, except for his self-produced albums were available at all, at the time. Since the time of this CD’s release in 1988, most of Bill’s commercial recordings for Mercury and other labels have been made available to the public in one form or another. Consequently, the audience for his art may have expanded considerably, It is high time, therefore, that the details regarding Bill Harris and this recording are better explained. This is not to denigrate the original liner notes by Washington Post columnist and reporter, Mike Joyce. Mike certainly knew Bill well, and had written about him previously. However, much was left out about Bill Harris and his many activities and talents and this neglect needs to be remedied.

Bill’s early years were spent around Nashville, N.C. He was born Willie Harris, Jr., on April 14, 1925 in Nashville, at the time a small community of under 1,000 persons. His father was, according to Bill, “a sanctified preacher”, and he enjoyed a religious upbringing. His mother, who played piano, taught him the rudiments of harmony, and very early on, he played organ at his father’s church. He also was exposed to the clarinet and the trumpet, at this time. When he was twelve his uncle bought him his first guitar. It was at this time that Bill developed an interest in the blues, forbidden at home, although it was in that very same home that he heard his first records by Bessie Smith and Ma Raney. When he went into town he often had occasion to hear some of the street musicians playing in the popular Piedmont flatpicking or finger picking style that influenced his own playing later on in life. He started out playing bottleneck guitar, with little training but great enthusiasm. He did not flourish as a guitar player at this time and in fact, was so disappointed with his own progress at the instrument that he lay it down for a number of years. While he had a love of music, his professional intentions were to become a pharmacist.

At the age of 18, he entered the Army in the Engineers Corps, and was stationed in France and England for two years, prior to his release in September of 1945. While in the army he did play bugle, but was not otherwise involved in music. Upon his discharge, Bill moved to Washington, D.C., still intending to become a pharmacist, (he was actually enrolled to study pharmacy at Howard University for one year) but turned to music instead enrolling in the Washington Junior College of Music studying voice and piano. It was during his studies at Washington College of Music that he took up guitar again, and upon graduation in 1948, his professor, James L Eubanks suggested that he continue his studies with the pre-eminent classical guitar teacher, Sophocles Papas, a close friend of Andres Segovia. Sophocles Papas taught at the Columbia School of Music, a school which he owned and that did not accept black students, at that time. Bill pressed on and finally convinced Papas to take him on, thus becoming the Columbia School of Music’s first black student. At the same time, Bill Harris became a full time professional musician in Washington D.C., gigging with jazz groups, as well as teaching, and of course, continuing his studies in classical guitar at Columbia, while also teaching there.

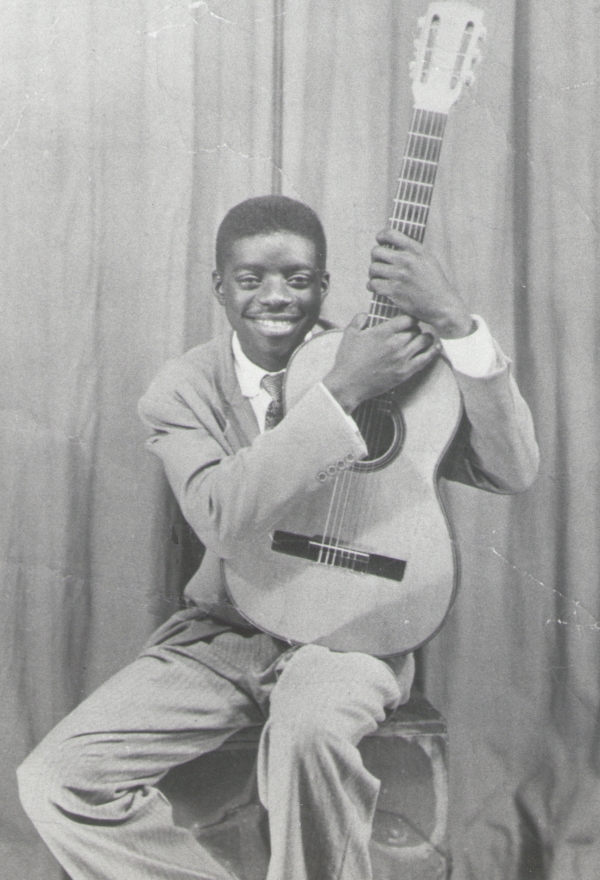

Young Bill Harris, year unknown.

Bill’s studies of classical guitar continued through the years, even as he went on to play professionally. It had great influence on his first jazz recordings in the mid-1950’s and he was especially moved by the opportunity he received to play for Segovia. Sophocles Papas brought Andres Segovia to play for and to attend a student recital. Bill was, like all of the other students, called upon to play, but was unusually reticent. He managed to put off his performance until most of the other students had performed. He had asked Papas to perform a jazz selection, but his teacher ignored the suggestion, referring him back to the classical pieces that he had been studying. When he finally performed his piece for the recital, he played a jazz selection, anyway. Segovia was impressed and complimented Bill, which pleased him enormously and earned Segovia his unending approbation and admiration. At the same time that Bill was a student, he was also teaching guitar at his former alma mater, Washington College of Music. In the late 1960s and for many years, he was a member of the faculty at Howard University School of Music and taught at Federal Community College.

By late 1948 or early 1949, Bill took a job with the James E. Strates shows, as a guitarist, soloist and arranger for their production of the Irwin C Miller’s "Brown Skin Models", a vaudeville Zigfield Follies style review glorifying attractive black women that traveled the country first on the Theater Owner’s Booking Association circuit, but later on performing at many venues, especially USO shows during and right after the war and under the banner of the James E. Strates organization.

By the end of 1950, Bill Harris joined the Washington D.C. vocal group, The Clovers, as their guitarist and arranger and his blues and jazz inflected playing had a major influence on their sound and contributed to their securing a recording contract with Atlantic Records in early 1951. One of the first recording dates the Clovers made after he joined the group featured the composition “Don’t You Know I Love You”, which was credited to Ahmet Ertegun on the record and in the publishing registrations, but which has often been credited informally to Bill Harris. To be fair, Bill had been hired as an accompanist and arranger, and his arrangements can be heard on many of the early Clovers recordings including “Fool, Fool, Fool”, “Lovey, Dovey”, “Blue Velvet” and many more. Undoubtedly, Bill participated in the creation of many of their hits and his contributions would today clearly be regarded as at the very least joint authorship. However, at the time he made no official claim to any original compositions that were recorded by the vocal group. During this period in his career, his playing was no-nonsense straight-forward rhythm and blues, not unlike that of Johnny Moore, Pete Lewis, Gene Phillips and many others who were highly skilled at this. He stayed with the Clovers for the better part of 7 years. In 1955, various musical shorts were made by a company called Studio Films Inc some of which feature the Clovers. These were produced and released both in theatrical versions and for television syndication in shows entitled “Show Time at The Apollo” and in the films, “Rhythm and Blues Review”, “Rock and Roll Review”, and “Basin Street Review”, as well as individual clips that were broadcast to fill 2 and 3 minute slots. Today many of these can be viewed on You Tube, in varying degrees of quality and all of the Clovers’ telescriptions give a good idea of Bill Harris’s playing, in this case employing what appears to be a 1954 Fender Telecaster .

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AncDQ4Dfvb0 (“Fool, Fool, Fool”)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MHsePlFPLLE (“Little Mama”)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XL6PgxKPCM8 (“Your Cash Ain’t Nothin’ But Trash”)

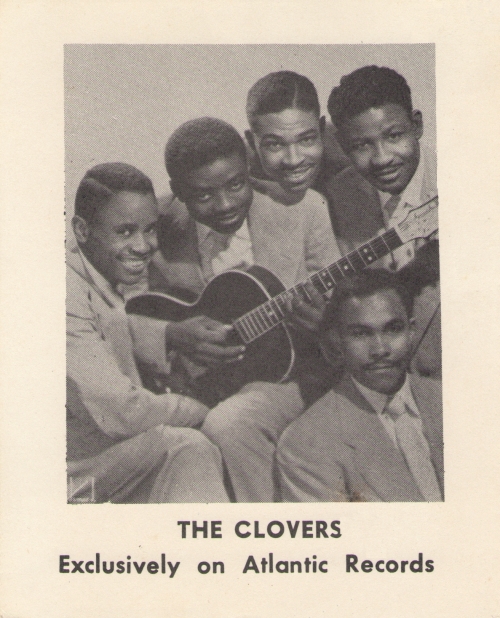

"Clovers" promotional coaster.

By 1956, Bill had been on the road for most of the previous 6 years, and was longing to develop beyond the rhythm and blues idiom. He had continued to study, whenever possible, with Sophocles Papas, and had spent a great deal of time with blues artists like B.B. King and Lowell Fulsom. He was close friends with Ray Charles and with Cannonball Adderley. He was ready to go off in another direction, and in fact had the good fortune to come to the attention of fellow guitarist Mickey Baker, while practicing in a dressing room, which notice led to Bill’s first recording date as a solo jazz artist for Mercury, in 1956. The date is not certain, but the first review of the release was published in the February 21, 1957 issue of Billboard, which noted the classical influenced acoustic guitar style as a departure from Bill’s previous work with the Clovers. The liner notes to the album also refer to the year 1957, so it obviously was not released until then. The album was reviewed by Nat Hentoff in Downbeat, and enjoyed reviews in High Fidelity, in the New York Times, in the Washington Post and even in the Army Times! The release, Emarcy MG 36097 features just Bill Harris performing solo on acoustic guitar and was entitled “Bill Harris”.

Later in May of 1957, Bill recorded material that, in combination with one unreleased track from his previous album’s session, was released on another Emarcy album, MG 36113, “The Harris Touch”. Unlike his first album, this album featured a quintet, with Hank Jones on piano and celeste. The first two Emarcy albums were followed by a third, possibly recorded as early as 1960, but definitely released prior to February 24, 1962, when it was reviewed in Billboard: Wing 16220 “Great Guitar Sounds”, again featuring Bill Harris performing solo acoustic guitar. All of the reviews for Bill’s recorded output for Mercury were quite positive. He was applauded for his classical music influenced jazz technique which required a sophisticated harmonic understanding, while preserving an infectious rhythm. Nat Hentoff in his Downbeat review of Bill’s first album duly noted:

“ No record this year is likely to be as welcome a surprise as this one……….The performance is a rare pleasure. The full-colored natural sound, for one thing. And there is the blues-soul of Harris which courses richly through everything he plays.”

Nevertheless, sales were not rewarding enough to embark on a performing career as a solo jazz artist, so Bill pursued a calling to teach. For most of the remainder of his life, Bill taught jazz guitar from his own Bill Harris Studios, first in his home and later in the old Strayer Business College building at 721 13th Street, NW Washington D.C. In 1957, right before leaving the Clovers, Bill published “The Harris Touch”, a self- teaching method book for guitar that he used in his private lessons. In the early 1970’s, Bill Harris joined the faculty at Howard University School of Music.

The three Mercury releases were not Bill Harris’s only recorded output. In December of 1962 he recorded a live performance at Washington’s Caffritz Auditorium. In 1965 or 1966 he released the album, “Caught In The Act” on his own label, Jazz Guitar. This was also a solo guitar effort. For many years, Bill kept this album in print, selling it by mail order and through the Bill Harris Studios. In the early 1970s, Bill had the good fortune of being noticed by producers for the French jazz label Black & Blue. They released, first a concert he recorded in Philadelphia, in June of 1972 as “Down In The Alley”, Black & Blue 33.042. This was followed by a tour in France, , during which he made a studio recording for Black & Blue, “Rhythm” released as Black & Blue 33.062. Bill also produced another album for his Jazz Guitar label, Jazz Guitar BH 751 “Bill Harris in Paris Live! Alone!”, which he released in 1974 and which consists of live recordings from his tour of France in 1973, and possibly live recordings he made in the US, as well. This brings us around to the CD to which the liner notes pertain, were it not for two activities which were a large part of Bill Harris’s life, each one enough to make a career of, and for which he earned many devoted fans and friends.

The first was the blues and jazz club that he established and ran off of Rhode Island Ave, NE, entitled “Pigfoot”. Ever since the late 1960’s Bill and his wife Fannie had organized a private club of sorts in their home, calling it “Hog Meat”, which became very public and hence risked bringing unwanted attention. Bill decided to make a go of it for real and located a place on Hamlin Street NE, near his home. At first, he was the victim of a real estate scam and his deposit was ripped off. Eventually, in 1975 he secured the premises at 1812 Hamlin Street, NE and “Pigfoot” officially opened. The club served as both a blues and jazz venue and served up soul food and ribs. John Malachi, fellow North Carolinian, who had a long distinguished career starting with Billy Esckstine’s legendary band and continuing on with Illinois Jacquet, Louis Jordan, Dinah Washington, Al Hibbler, Sarah Vaughan, and many others was often in attendance at the club holding down the piano chair when the jazz school was in session. His counterparts at the keyboard holding down the blues side of the house included Sunnyland Slim or the young Harmonica Phil Wiggins, who performed at the club almost as regularly as John Malachi’s weekly jazz tutorials for young up and coming jazz musicians. During this period, Oscar Peterson and Sarah Vaughan were as likely to drop in, when they were in town as Kenny Burrell, Shirley Horn or Charlie Byrd, who regularly performed there. In fact, Pigfoot was so famous that in 1979, the mayor of Washington, D.C., the honorable Walter Washington and the Washington D.C. city council declared by proclamation, November 4th permanently, “ Bill Harris - Pigfoot” day in honor of Bill Harris and the club. The good times, as they were, did not last forever. Pigfoot was located in far out NE Washington, a very nice area, but off the beaten track for most blues audiences which at the time were primarily young and white. Had it been in Georgetown or Dupont Circle, Bill would have been rich. Alas, in time, money problems came to the party. In 1981, the IRS charged Bill Harris with a “withholding tax” delinquency that ended up amounting to over $30,000.00! These are the taxes that employers pay to the Treasury so that the US can be certain that their employees will actually pay their income taxes and are better known as “payroll deductions”. It does not matter whether the deductions are made and not remitted or not even taken out of the employee’s pay. To the IRS, failure to make these deductions and payments is perhaps the most serious offense that any taxpayer can commit! The club was seized and auctioned off. Bill was left with an outstanding federal tax bill that he would not discharge until he was forced to sell off his home in 1987, just over a year before his untimely death. This kind of outcome would be very unlikely today, as taxpayer protections have been enacted, but in the late 1980’s this result was not uncommon. Pigfoot was a wonderful scene and it’s shocking end and even worse consequences were a terrible tragedy for everyone who knew Bill Harris.

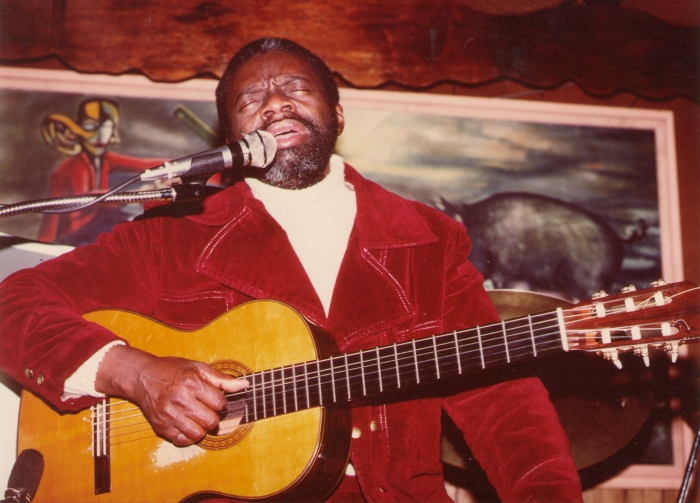

Bill Haris at "Pigfoot", during the late 1970s.

As though all of this activity in one, often under-appreciated and sometimes beaten down lifetime were not enough, in addition to being a club owner, professional musician, in-demand music teacher, performer, and to vocal group enthusiasts and guitar fans, a living legend, Bill Harris was a very popular disk jockey on Washington, D.C. fm radio stations. The show he hosted was called “Hootie Blues” and featured a substantial amount of acoustic pre-war blues; frequent musical exposes of various guitarists, both blues and jazz players via records and bios; exposure to poetry of the Langston Hughes and other Harlemite variety; and anything that might come up or occur to Bill that day or in the previous week since the last time he was on the air. His shows ran during most of the mid to late 1970’s and early 1980’s. These were heady times for Washington D.C radio. Petey Green was on WOL and WYCB. Felix Grant had “The Album Sound” on WMAL. Dick Lillard gave his historic R&B and vocal group exposes three and four hours a week first from Georgetown’s WGTB and then Bethesda’s WHFS. Yale Lewis had his weekly Saturday night seven hour show on WETA. Bill hosted “Hootie Blues” first on WHUR, then on WGTB before finding a permanent home at WPFW, the local Pacifica affiliate and primary 24/7 jazz radio station serving the D.C. market. It was a weekly three hour or four hour show, depending on which year and which station was broadcasting it. At WPFW, during the late 1970’s and early 1980’s, it followed Jerry Washington, “The Bama”’s three hour Saturday morning show. Bill’s show had been on the air for quite a few years before Jerry Washington started his, but both dedicated a bit of their time to the life and experience of rural black America, the Bama with his patter and chatter, though not his music, while Bill gave the listener practically the only exposure to country blues on the air in Washington D.C., at the time. Jerry Washington’s “Bama” persona was a put-on, of course. There was nothing rural about him. Bill, on the other hand, knew whereof he spoke and did so without affectation. These DJ positions at WPFW were largely unpaid, with some exceptions. This was of little importance as the reputation of personalities such as The Bama became widespread. Bill was already a well-known contributor to cultural affairs in Washington, D.C., so his role and manner were more subdued, primarily that of educator, in keeping with his guitar teaching work and the many cultural and educational activities he hosted at Pigfoot and elsewhere. As in everything he did, Bill was quite modest. Although he personally knew more artists and personalities than any of his fellow radio hosts and had extensive front line experience as a professional musician and performer, he never used this to advance his own importance or create a public persona. He did plug Pigfoot and the various fund raising picnics that he would be sponsoring, but it was almost always in the context of a public service announcement or in the course of providing information on educational opportunities such as the free jazz clinics and jams he hosted for the benefit of anyone willing to participate.

This brings us to the CD to which these words are a background. The program begins with the kind of opener that over the years, Bill would start off many of his performances on stage, if they were of the blues variety. This one is a medley consisting of a holler type recitation entitled “Blues Ain’t Nothin” and a performance of Big Bill Broonzy’s “Key to the Highway”. This was performed and recorded at a concert given at Blues Alley on June 26, 1982. Blues Alley, in the heart of Georgetwon is and was a very successful jazz (and blues) venue in Northwest Washington D.C., just about as far as you can get from the Pigfoot, out in far Northeast Washington. “Blues Ain’t Nothin” is the start of many songs, examples of which are found in recordings or sheet music by Ida Cox and Lovey Austin, Lasses White, Georgia White, Son House, Willie Brown, Memphis Slim, Mississippi John Hurt, and dozens more. In Bill Harris’s version the line is completed in the first verse with “..but a woman on a poor man’s mind..” somewhat similar to Blind Lemon Jefferson’s “Corinna Blues”, which uses “..but a good woman on your mind..”. The second verse Bill uses “poor man’s heart disease”, closer to Georgia White’s original “a low down heart disease”. From Bill Harris it exhibits one of his earliest performance skills, a yodeling holler that he used to practice back in Nashville while growing up. Here he starts the concert beginning the song off stage and walking on as he completes his introductory verses and segues into the Bill Broonzy classic, “Key to the Highway”. “Key to the Highway” was not recorded first by Broonzy, pianist Charles Segar recorded a version for Vocalion prior to the recording by Broonzy and Jazz Gillum, which is the version performed by Bill Harris here. However, it is generally recognized that Broonzy is its author, if not in whole, at least in major part.

The second selection on the CD is also a medley, this one consisting of a recitation, followed by another classic blues, The Mississippi Sheik’s “Sitting On Top of the World”. “The Bill Harris Blues Monologue”, the recitation portion, is the story of how he came to be introduced to the blues, or at least a comical version of it, involving his neighbor George Daltry and the Ku Klux Klan. “Sitting on Top of the World”, originally composed by Walter Vinson and Lonnie Chamton and recorded by the Mississippi Sheiks, was later also recorded by Big Bill Broonzy, Milton Brown, Doc Watson and most notably Howlin’ Wolf. This version, Bill tells us is the “…George Daltry, Mister Blake, Big Boy Cruddup, Peetie Wheatstraw, the Devils Son In Law, Blind Blake, Leadbelly…” version! (“Devil’s Son inLaw” refers to Peetie Wheatstraw’s complete stage name as it appears on many of his records. Bill does not use any of the “Ooh, Well, Well” characteristic of Peetie Wheatstraw’s songs). We are also treated to a deft chorus of Bill’s whistling, before he breaks into the guitar’s accompaniment to his vocals. Bill does not play in the Piedmont finger-picking style in either of the blues songs he performs here, so they are not evidence of this influence in his playing. Rather, his performance is more in the Mississippi delta style, displayed on the version that he credits finally to Leadbelly, though his version does not really resemble Leadbelly’s style, who is not known for a recording or performance of “Sitting on Top of the World”. Neither are any of the other artists he mentioned! What we really get is pure Bill Harris!

The third selection completes the blues portion of the program, not with a blues song, but rather by a recitation of a poem entitled “Ma Raney” written by the great poet Sterling Alan Brown and published in 1932 in his collection entitled “Southern Road”. Sterling Brown was a native Washingtonian, with a distinguished career teaching poetry and literature at Howard University. During the latter years of Brown’s tenure, Bill Harris was teaching guitar at the Howard University School of Music, and they lived in the same neighborhood of Brookland, in NE Washington, D.C. Sterling Brown also performed at Pigfoot, reading his poems to the accompaniment of Sunnyland Slim. As is evident, Brown had a great affinity for the folk speech patterns of the southern sharecropper, and captured the energy and excitement that the arrival of Ma Raney, Queen of the Blues, engendered wherever she performed. Bill truly does justice to this wonderful poem.

In 1957 or probably early 1958, Bill Harris performed at the Village Gate in Greenwich Village, a program that he titled “Bach to Blues”. Tracks 5 through 8 are from a performance of this program at the club. For Track 5 we have included an example of Bill’s classical playing. “Bach’s Prelude in D Minor” was arranged by Andres Segovia, as were all of the other classical works that were performed by Bill during that concert. Segovia was known as a very strict teacher, who required dogmatic observance of his methods and approach by his students. Bill, who would have been called upon to display his classical guitar technique to Segovia had he performed works suggested to him and taught by Sophocles Papas during the recital, escaped likely criticism and reproach from the master by performing a jazz selection that earned him praise instead. Track 6 includes two selections, “Spring” and “Golden Sunset”, both compositions having been performed and recorded during the studio sessions that form the basis of the first two Emarcy releases. In fact both were included in “The Harris Touch”, which was released in the later part of 1957, so the concert version included here probably would not have been recorded earlier. During the concert, they were performed in quick succession, much as they are featured here, and are great examples of Bill’s compositional skills at the time, although to be fair “Golden Sunset” was actually written by pianist Lonnie Hewitt, who went on to perform and record with Cal Tjader during the mid-1960’s. Tracks 7, 8 and 9 display Bill’s rendition of standard jazz material: “Satin Doll”, “Out of Nowhere” and “Stomping At the Savoy”, which are performed skillfully and with enthusiasm as were all the selections from this concert. At this time, Bill took fewer risks and his approach was more structured and less spontaneous than later on, displaying a more practiced technical approach, that is clearly evidenced on his Emarcy recordings.

Track 10, is a version of the Bill Harris original “Possessed” recorded at the same 1982 Blues Alley concert that provided the blues material that starts this CD. This composition had been part of Bill’s repertoire for many years having been performed and recorded for the first Emarcy album released in late1956 or early 1957. This was dedicated to his wife Fanny as an expression of his devotion to her, and is the first of two compositions on this CD that are dedicated to her.

For Track 11, we are introduced to Bill’s more modern jazz style with Coltrane’s “Syeda’s Song Flute” from a concert at the American Theater performed on June 28, 1975. The American Theater is the original name of the Sylvan Theater on Rhode Island Ave, NW, that had become the primary venue for a theater and performance art project funded by Howard University, in the early 1970’s. They had vacated the theater by the end of 1973, and it had become available for rental by anyone interested in putting on a performance there. This is probably where this concert took place. Here, the approach is obviously much more modern than in all previous selections on this CD. Bill had recorded “Syeda’s Song Flute” previously, first a live performance in February, 1972 at Cramton Auditorium at Howard University, and later on at a live concert in the fall of 1973, that he released on his own label Jazz Guitar’s “Bill Harris in Paris, Live! Alone!”

Track 12 is another recitation, this one of the poem “Jazz Band”, by Frank Marshall Davis. The poem was first published in the 1935 anthology of Frank Marshall Davis poems entitled “Black Man’s Verse”. Davis was an important poet, primarily identified with Chicago, a friend of Langston Hughes and Sterling Brown, and in more recent years an inspiration to a young Barrack Obama. Although Davis is primarily identified with Chicago during his early career and the poem was first published in Chicago’s Black Cat Press, the poem was written and published while Davis was editor of the Atlanta Daily Word. Davis would go on to become prominent in the South Side Writer’s Group with Richard Wright. This recording by Bill Harris was also a part of the June 26, 1982 Blues Alley concert from which several selections on this CD were culled.

Tracks 13 and 14 consist of two of the three movements of a jazz concert piece composed by Bill Harris and devoted to the guitarist Wes Montgomery, simply entitled “The Wes Montgomery Suite”. “The West Montgomery Suite” was written by Bill Harris while he was the recipient of a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship for Jazz Composers in 1972. At that time, he was teaching guitar at the Howard University School of Music. It was first performed at a Faculty Recital held at Howard University’s Cramton Auditorium on April 21, 1972. The suite consists of three movements, “Remember Wes”, “OdetoWes”, and “Sweet Fannie Louise”, the first two movements obviously named for Wes Montgomery, but the last dedicated to Bill’s wife, Fannie, included in the composition because Wes had expressed immense gratitude to Fanny for her fine cooking, while he was staying at the Harrises, during one of his many visits. The April 21, 1972 performance was performed by Bill Harris with the Howard University Ensemble, and the arrangement was written by Rick Henderson, who also led the orchestra during this performance. Rick Henderson was an arranger for Duke Ellington during his Capitol years, who had led the Howard Theater house band (not connected to Howard University), and was writing arrangements and leading various orchestras in Washington D.C. and Maryland, at the time of this recording. Track 13 of the CD is from this performance. Track 14, on the other hand, was from the concert that Bill gave at the American Theater on June 28, 1975, where he performs this movement as a solo artist. Most of Bill Harris’s output as a jazz guitarist, in fact as any kind of guitarist, other than as an accompanist for the Clovers, is of the solo variety, and it is only fitting that the last selection on this CD should reflect his chosen method of performing.

|